Mutations (unintended changes or typos) in one of two genes (PKD1 or PKD2) account for most cases of ADPKD. Recently, researchers discovered a new gene, GANAB, that’s believed to cause polycystic liver and kidney disease as well. Mutations of the first gene, PKD1, are the most common and account for about 85% of ADPKD patients. However, in about 7% of patients, it’s not possible to determine which gene mutation is causing the disease.

The PKD1 and PKD2 genes encode the proteins polycystin-1 and polycystin-2, respectively. These two proteins interact to regulate cells in the kidneys and liver, play a role in forming tubular structures, and influence growth and fluid secretion function. Mutations of the PKD1 or PKD2 gene create cells with abnormal functions and ultimately result in the cyst growth common in ADPKD.

Clinicians observed a big difference in the severity of kidney disease depending on which gene is affected.

- Patients with PKD1 mutations have bigger kidneys, more kidney related complications, and require dialysis at an earlier age compared to those with PKD2 mutations (55 vs 75 years, respectively). More recent studies also identified a subset of PKD1 patients with milder kidney disease in which their mutations do not seem to completely inactivate polycystin-1 function. This is called a non-truncating PKD1 mutation.

- Patients with PKD2 mutations not only have a milder disease but a later onset of symptoms which can lead to delayed diagnosis.

- DNAJB11 and IFT140 mutations can also be a rare cause of atypical ADPKD, and other mutations are being studied. Learn more about the genetic causes of ADPKD here.

Determining the specific gene mutation you have requires genetic testing. This type of testing isn’t typically covered by health insurance and could be costly (several thousand dollars). Diagnosis with ADPKD is mostly done through imaging (CT, MRI, or Ultrasound) to look for cysts, and genetic testing is usually reserved for atypical cases or to rule out ADPKD in a young potential kidney donor. If you’re interested in getting a genetic test, talk to your doctor or find a PKD-specialist here.

-

How is ADPKD inherited?

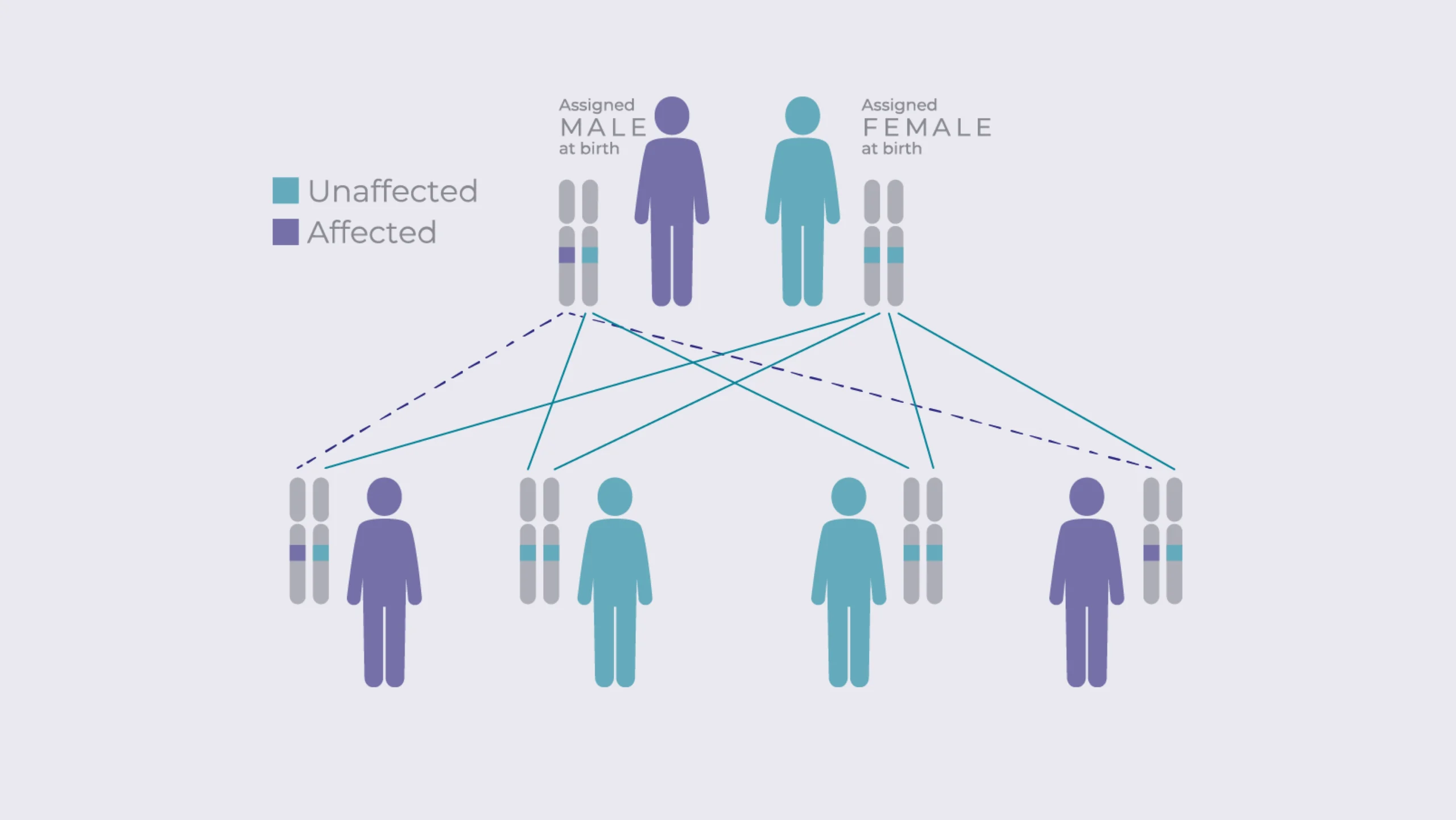

The term “autosomal dominant” in ADPKD refers to two important features of the disease. First, because the disease genes reside on an autosome (i.e. PKD1 on chromosome 16 and PKD2 on chromosome 4), both male and female at-risk patients have an equal chance of inheriting ADPKD. This means a parent with ADPKD has a 1 in 2, or 50%, chance of passing the disease to their child. However, the number of affected children within a single family is entirely due to chance and may or may not be 50%. The reason we call this form of PKD “dominant” is because it can only take one copy of the mutated PKD1 or PKD2 gene from one parent to cause ADPKD.

Four to 10% of patients with ADPKD may have “de novo” disease due to a spontaneous mutation. Typically these patients don’t have a family history of ADPKD. Their disease is due to a spontaneous mutation of the PKD1 or PKD2 gene in one of the germ cells (i.e. egg or sperm) of one of their parents that then gets passed on to them. Individuals with “spontaneous mutations” become the founders of a bloodline with a 50% chance of passing it on to future generations.Most of your body cells carry one normal and one mutated copy of the ADPKD gene. However, when sperms or eggs are formed in that person, only one of the two copies of an ADPKD gene is passed on, typically with equal chance. Only the sperms or eggs that carry a mutated PKD gene can pass on the disease. This is why the chance of disease transmission to your children is typically 50%.

-

Will a person with a mutation for ADPKD always have the disease?

Yes, the genes for ADPKD are dominant, which means that inheriting only one mutated copy of the PKD1 or PKD2 gene from an affected parent is sufficient to cause the disease. There is no carrier state with a dominant disease, and it doesn’t skip a generation. This means the disease will eventually manifest as you get older and all generations in a family have the potential to be affected. If you have a mutation, at some point in your life at least some of the symptoms of the disease will probably occur, although they could be very mild. When an at-risk individual doesn’t have a mutation for ADPKD, they aren’t affected and the disease cannot be passed to the next generation.

This doesn’t mean that everyone who gets the ADPKD gene will have the same signs or symptoms or the same course of the disease. There’s a wide spectrum of severity within ADPKD. At one end are children who are diagnosed before birth or in the first year of life with cysts or big kidneys. At the other end are people who have few symptoms, even when they’re much older. It’s important to note that some individuals (especially those with a PKD2 or non-inactivating PKD1 mutation) are more likely to live a normal life span and die of other causes before there’s a need for dialysis or transplantation. A majority of patients with ADPKD will fall in the middle of the spectrum, and at some point in their life they’ll have some signs or symptoms associated with ADPKD.

-

Will everyone with a mutation in the same family have the same type of ADPKD?

Yes, all affected ADPKD patients with the same mutation in a family will have the same type of ADPKD. However, their signs, symptoms, and course of the disease are often different. The most dramatic example of this occurs in families with children who are diagnosed before birth or in the first year of life. These children have symptoms long before their parents. Sometimes the parent may not even be aware they have ADPKD until after their child is diagnosed. Significant kidney disease variability within ADPKD families suggest other genetic and environmental factors can modify the severity of this disease.